By Will McGuirk

Do you remember rock ‘n roll? Steppin’ out, blue dress on, pink carnation, that night in Toronto? Does it seem so long ago now, and wow was a book ever so relevant as Jonny Dovercourt’s ‘Any Night of the Week’?

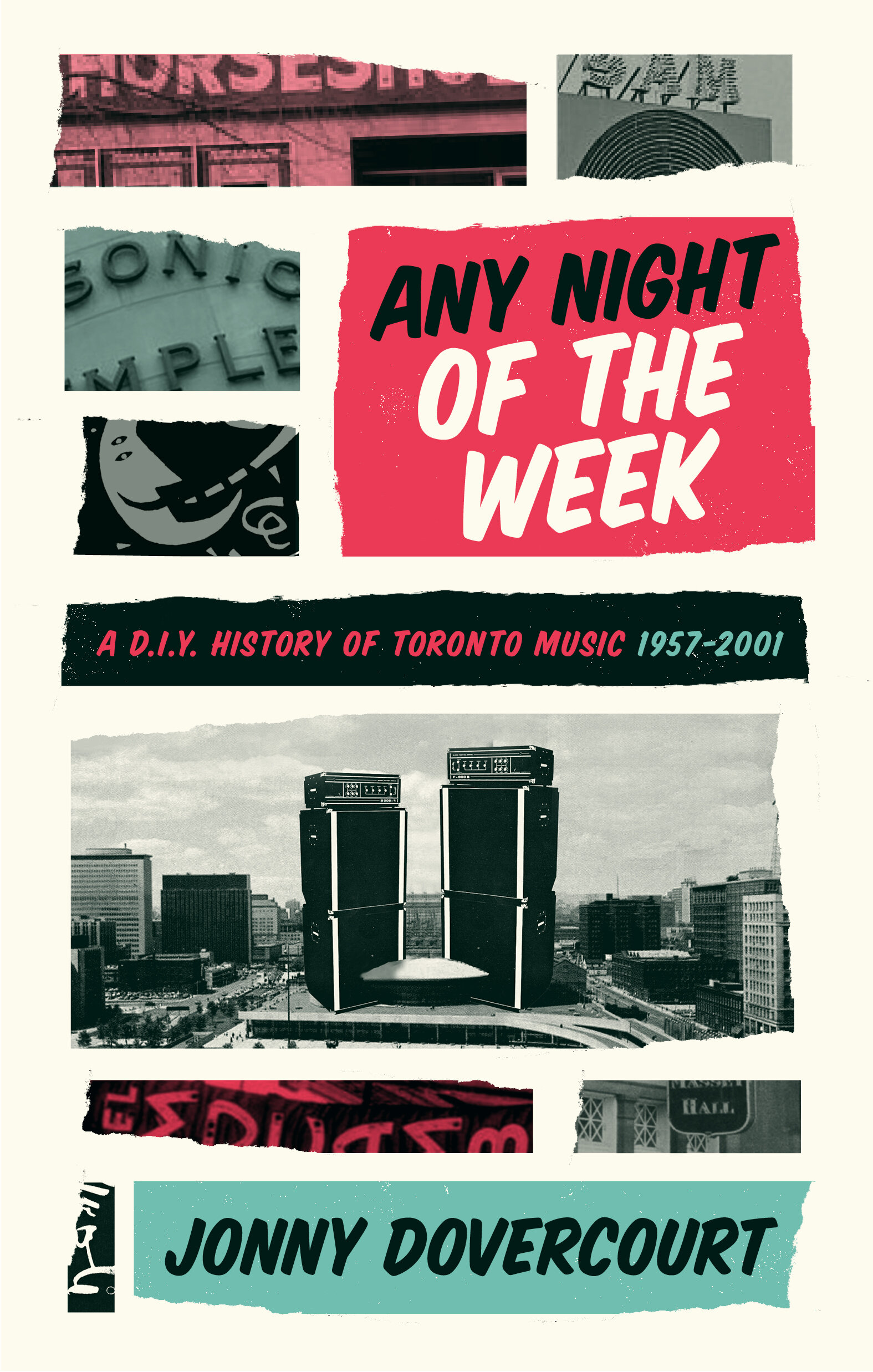

Dovercourt’s book, a history of Toronto’s D.I.Y. culture, explores the communities which gathered around new bands and the stages they played on, and it’s a delight to visit, and in some cases revisit, those thrilling nights and recall what a blast it was to go out and make friends of strangers and the you-had-to-be-there earworms which got us through the daily grind. He lays out the lineage and legacy of Hogtown’s seminal acts, by way of their club beginnings, from 1957 to 2001, from Ronnie Hawkins & the Hawks to Broken Social Scene, weaving a tale of the city’s underground scene as interconnected as the overhead wires of the TTC. The book is published by Coach House and for your Covid-19 convenience Jonny has also compiled a Spotify playlist as well.

Jonny is co-founder of the two decade long 100% D.I.Y. indie to its core Wavelength Music Series and in ‘Any Night of the Week’ he completely avoids anything which reeks of industry organized nights out, and opts instead for deep dives into those start-up promoters, some of whom grew into major players, and the venues they discovered and converted. What Jonny’s book speaks to is the agility of the do-it-yourselfers, their tenacity, and drive as well as the creativity of the musicians and promoters who for the most part had one foot solidly in the city’s art scene. For TO punks, and we will use that in the outlier sense, it was all about freedom of expression, of enabling voice, and if the scene was politically motivated it was in the search for some kinda fun in dour faced Toronto the Good.

The role of the music industry is important, it has to be noted, as it is bait for musicians from all over the country lured by the promise of glittering prizes . Many acts ‘based in Toronto’ have members originally ‘hailing’ from in some cases, Durham Region and the D-Rawk’s own entrenched D.I.Y scene is a vital resource to fuel the big city. Dovercourt can not be expected to know the all of every small town’s scene, but there are welcome shout outs to a couple of places and bands I have fond memories of, including Pizza Pino and Kat Rocket.

Dovercourt states at the onset this is just one thread of history, his story. It is granted a well-researched and well told story but still his. He does speak to indie and punk and the city’s hip hop scene’s roots in reggae but metal is less his thing so its not covered. The book is not comprehensive but in the context of Canada, honestly can anything ever be?

'Any Night of the Week’ is informative but also inspirational so buy it, read it, dig it, dream it and then get to work.

We sent Jonny some questions and he generously answered.

Slowcity.ca: Tell me a little about yourself, where you were born, how you got into music and in particular what turned you onto indie/alternative?, and also why you chose writing?

Jonny Dovercourt: “I was born in Scarborough. My parents played a lot of Beatles around the house. I wasn’t much of a musical child - hated piano lessons, barely made the cut for school band - but I really got into pop radio (1050 CHUM) around Grade 4. My older sister turned me on to CFNY (aka 102.1 The Edge), where I got into the usual alternative fare like New Order, The Smiths, Depeche Mode, The Cure, etc.

“This coincided with the rise of music videos, and I think that was the biggest conduit for me - even prior to MuchMusic launching in 1984, there were video shows like Toronto Rocks and Video Hits, which aired after school, and the original incarnation of CityLimits (later Much’s alternative video show), which aired late at night, but was re-run on Sunday mornings. In terms of what drew me to indie/alternative, I think what’s funny is that I didn’t really realize what I was seeing wasn’t what most people considered “normal.” I did have the sense I was getting a window into a more “adult” world that was otherwise off-limits. I was also a sci-fi nerd, so I was attracted to things that were a little weird or different in sound or look, though tuneful musically.

“MuchMusic played some pretty out-there stuff during regular programming hours, and that’s where I first heard the Sex Pistols, as well as gonzo local indie video likes “Apple Strudel Man” by Jolly Tambourine Man. I started my first band in Grade 9, after befriending a classmate, Dave Rodgers, who was the only other person I knew who was into punk. We could barely play when we started, but Dave was a prodigious songwriter at a young age, we had ambitions that far outstripped our talent. We jammed in the basement and released a handful of home-recorded and home-dubbed cassettes. It was super D.I.Y., but we didn’t even know what that meant.

“There wasn’t much of a music scene for original bands in Scarborough at the time. We played our first gig at our high school, at a United Way benefit concert - which became an annual event I ended up helping organize - the beginnings of my “career” as both musician and promoter!

“My high school band played a few gigs downtown, and our first one was the most memorable - we played an Elvis Monday at the Soup Club (aka the Slither Club), a club I wrote a bit about in the book - it smelled like raw sewage, as there had indeed been a sewage leak. I’ll never forget the look on my Dad’s face when he came to pick us up (bless that man). It was through Elvis Mondays organizer William New that I discovered the 1150 Queen West scene, after he started booking that club in 1991, and that’s where I made friends with people like Brendan Canning and Noah Mintz (then of hHead). It was a really happening scene, and really welcoming, and that’s how I first found my place in the local music scene.

“As far as writing goes, I started writing about the local music scene (mostly) for my university newspaper, The Gargoyle. I devoured Now Magazine and Eye Weekly every Thursday, and also wrote a few reviews for Exclaim early on. Alternative media was also really my window into the larger world of culture. I started an internship with Eye after finishing undergrad, and became the listings editor, which really set me off on both my writing and arts presenting careers. I worked at Eye for five years, which was an amazing cultural education.”

SC: How long did the book take you to write?

JD: “The book took me four years to write! The idea of doing a Toronto music book had been bouncing around my head since about 2009, but it took a while for me to decide to sit down and do it. I came up with the concept and outline and pitched it to Coach House in the fall of 2015, and started working on it in 2016. The book went through a few different structures and working titles before we found a format that really worked. It took a lot longer than I originally expected to research and write, which is unsurprisingly given the breadth of the timeline, and that I was writing it as a passion-project/side-hustle while running Wavelength as an arts organization full-time. I handed in my manuscript in October 2019, pretty much exactly four years after I first pitched it.”

SC: The book finds its base in the architecture of the scene, and it gives a physicality to the music, - why did you choose that approach?

JD: “The structure really emerged as I got into writing the book. Originally it was told strictly chronologically, but the early chapters I wrote jumped all over the place and would have given readers whiplash. As a lot of the research and writing were done hand-in-hand, and one theme that emerged was the strength of Toronto’s live music venues, at least in comparison to its anemic track record on record. It wasn’t until the 21st century that really vibrant, impactful homegrown independent labels were able to push local music out to the rest of the world. It was live venues that really created the fabric of the scene, as these were the meeting places for the community and where people developed their sound. You could really see the sound of Toronto music evolve as it migrated throughout different neighbourhoods in the city - from R&B and rock’n’roll on Yonge Street in the ‘50s to folk, blues and jazz in Yorkville coffeehouses in the ‘60s, to punk, reggae and new wave on Queen West in the ‘70s and ‘80s, to the blend of indie and electronic in and around College/Kensington in the ‘90s.”

“What I think unites Toronto music is a spirit of community or communitarianism, of artist-run, DIY self-determination. ”

SC: So many of Toronto bands are made up of members from elsewhere, it is the centre of the industry which is why people move there but do you think there is a "Toronto Sound" which has emerged from this confluence of sources?

JD: “Actually, I don’t think there is a “Toronto Sound,” and I don’t think that is something that’s either possible... or desirable! The city’s motto, after all, is “Diversity Our Strength,” and the city and its music scene are simply too large to get pinned down to one sound. There are too many cultural inputs, too many backgrounds and traditions, for one sound to dominate. A “City Sound” is really only possible in a smaller place, and for places where it has happened, eg. Seattle or Manchester - both of which are smaller cities than Toronto, it ends up being more of a curse in the end, a creative straitjacket for anyone from those towns who didn’t want to play grunge or “baggy” electro-rock.

“What I think unites Toronto music is a spirit of community or communitarianism, of artist-run, DIY self-determination. There’s also a high degree of musicianship and technical excellence, in part due to our strong public education system and arts/music programs in schools. But there’s also plenty of sardonic, humourous, tongue-in-cheek goofiness, and artsy conceptualism. And there are certain sounds that dominated at certain times here, such as roots-rock in the late ‘80s / early ‘90s. And that was happening at the same time as hip-hop was starting to emerge here, in other parts of the city besides Queen Street.”

SC: You steered clear of anything which smacks of industry, and really dove deep into the DIY (street level and below) scene - why does that scene matter to you and why are you so invested in its survival?

JD: “Because I think it’s where the most interesting music was (and is) being made. I never felt much connection with the music industry - or rather the recording industry - as it always felt peripheral to me; this thing you knew was there, but never really encountered directly. I don’t think the A&R guys were coming to the same shows as me and my friends! And I can understand why: the Canadian major labels were a branch-plant economy, without a lot of power, and they were looking to sign things that were going to be profitable. And there wasn’t a lot of crossover between anything that fit that bill and what excited me. The industry wouldn’t touch Fifth Column or Rent Boys Inc. or Phleg Camp. . . or even Ghetto Concept - who won Junos and had videos in regular rotation on Much! Musical innovation is always artist-driven and coming from DIY initiative and energy.”

SC: On the Facebook we had a chat as you saw about the pizza place, Pino Pizza, in Ajax, it was a lot of fun there, - in your research are there similar places in other small towns around the GTHA which you found just as bizarre or interesting?

JD: “Pizza Pino’s was by far the most bizarre and interesting of the GTHA all-ages venues that I was aware of. I heard about it back in the 1150 days, but only after shows there had been shut down, and I was a bit bummed, because it sounded like exactly the scene I was looking for while playing with my high school band in Scarborough, and we weren’t even that far away geographically! So Pizza Pino’s became a bit of a mythical “white whale” for me. In terms of the ‘90s small-town all-ages scenes, they definitely seemed more fun, arty and weird east of the city, in more working-class places like Oshawa, home of Starkweather (a gnarly garage punk band named after a serial killer) or Cobourg, from which hailed Holocron, a post-hardcore band whose lyrics entirely concerned Star Wars. And probably the greatest Canadian post-hardcore band, Shotmaker, came from Belleville, before relocating to Ottawa - which also had a really amazing arty indie-rock scene with bands like Wooden Stars, the Spiny Anteaters, etc.

“West of the city, in the wealthier 905 suburbs like Mississauga, Oakville and Burlington, the all-ages hardcore scene was a lot more serious, heavy and straight-edge-influenced - this is the community that spawned bands like Chokehold, Grade, and (from St. Catharines) Alexisonfire. Totally vibrant scene, but less my cup of (herbal) tea, stylistically speaking.”

SC: The book is a great reminder of community importance and timely as we deal with this virus - what do you think the other side will look for your DIY scene, what music do you think will emerge, what will playing live look like and what venues will survive?

JD: “That’s a great question. And one that’s really hard to answer, as no one can predict how long this will go on for, and what the ultimate socio-economic cost will be. I think that music made solo will prevail in the short term - with social distancing and livestream concerts privileging singer/songwriters, hip-hop emcees, electronic DJs and experimental drone acts. “Bands” are definitely handicapped at the moment. You may see a huge boom in live venues, if this ends by the summer, people are stoked to go again, and the economy makes a quick recovery. Or they could all go out of business, if this goes on for a long time, we’re stuck in an economic depression, and we all forget how to socialize in collective physical space.”