Our children know all about the Underground Railway but now they will also be taught the history of the children the train passed by.

Secret Path is Gord Downie’s own journey into Canada’s closeted past and his singular desire to shine light on the hidden history of this country’s Indigenous peoples. His personal Truth and Reconciliation project tells the story of Chanie Wenjack, an Anishinaabe boy who died of exposure by a railway line, escaping from a residential school in 1966. Wenjack was twelve.

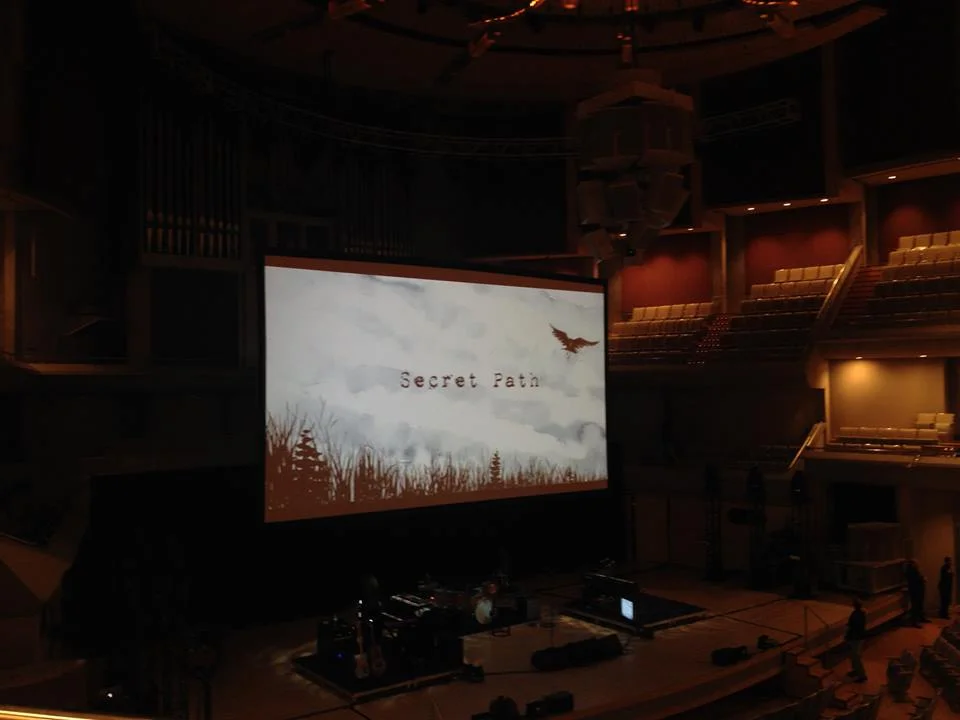

Photo by Jag Gundu for the Roy Thomson Hall archives

Downie has built a crew of about a dozen musicians, animators and illustrators to record an album of ten songs, create a graphic novel illustrated by Jeff Lemire, and produce an animated film, animated by Justin Stephenson, as well as a short documentary about Downie meeting the Wenjack family, a couple of weeks after the Tragically Hip’s final concert in Kingston.

Downie has terminal cancer but as the Secret Path album was completed a couple of years ago, the album says nothing of his present plight. Downie’s diagnosis only added urgency to the telling of Chanie’s flight and the project was kicked into overdrive. The film which normally would take upwards of a year to create was finished in matter of months. The album is available on Arts & Crafts, the book is out too and the film was screened at a special performance by the band at Roy Thomson Hall in Toronto and the National Arts Centre in Ottawa.

Although Chanie’s story is heartbreaking, Downie, and musical collaborators, Kevin Drew of Broken Social Scene and Liam Hamelin of The Stills, did not choose to create a soundtrack of sorrow. Secret Path is at times a joyful celebration of possibilities, of hopefulness, of the power of choice. Chanie’s story ended in tragedy but it doesn’t take away from the fact of his choosing and of his celebration of self. He chose his path and each slow cold shivering step along the railway lines in the Fall of 1966 was one step closer to his parent who loved 600 kms away.

The music roams from atmospheric hauntings to joyful pop. It is the strength of the percussion at its core that allows for the building of the soundscape beyond it. The album stretches out, it is a big country after all. But with always one foot on the ground, it is a big but sensible country after all. At bottom is one foot step after another, one beat after another; The album featured guests are Charles Spearin on bass, Ohad Benchetrit on lap steel, Kevin Hearn on keys and Dave “Billy Ray” Koster on drums. Drew, Hamelin, Spearin and Hearn were part of the band on stage at the screenings of Secret Path. They were joined by Josh Finlayson of the Skydiggers. However the album is not just a soundtrack, it stands on its own as an accomplished work. Even as a concept album the songs are contained within themselves, there are even tracks that would play well on radio, even ones to unabashedly dance to. It is a remarkable piece of art and look for it to dominate discussion of next year’s Polaris Music Prize.

Downie humanizes Chanie. The boy is a symbol perhaps, a possible icon, but he was just a boy. Drew’s production wraps the boy in a deep warm embrace, in the great epicness of Broken Social Scene’s collective sonic hug. The music feels like a companion on the boy’s journey, it is a friend to someone who doesn’t know a soul out there in the wilderness. The music walks alongside, instep with Chanie along his walk, as he dreams of his father, as he worries about the forest, as he faces down a hallucination of a looming black crow, (perhaps the black crow of Christianity, the crow priest of Joseph Boyden and the Black Robe of Brian Moore). The music settles in beside him as he stares into a fire, created with the seven matches he has with him, as he picks over bushes for the year’s final berries and he moves closer and closer to reuniting with his family but we also know, as does Drew and Downie, that each step is a step closer to his last moments.

Photo by Jag Gundu for the Roy Thomson Hall archives

There has never been anything like this that I can think off. Perhaps the sea to sea to sea multimedia broadcast of the Tragically Hip’s final show, using every channel possible to create an acoustic space for the whole country to inhabit. Downie has done something similar here, he has used it all; fame, music, books, film, architecture, drawings, talks, interviews, every possible mode of expression to tell the Wenjack tale. He has created an environment, this space of peace, and invited us all in to listen and to talk about Chanie the boy and all those like him.

“We have this great new house built, but, we have got someone locked up on the third floor that no one is talking about. The attic is off limits. That is Canada now. Who is up in the attic but the person living on the property where you built the house.” - Gord Downie.”

Chanie puts a face on Canada’s legacy of residential schools and on its history of cultural genocide. From the 1890s to the 1990s 150,000 children were placed by the feds in residential schools. 20,000 died, and that is 1990s as in two decades ago. But Canada is more geography than history says Prime Minister MacKenzie King.

History is past but geography is the ever-present and perhaps the most vital part of the Secret Path project is that the trail does not end when you close the book or resleeve the album. It begins.

History is the then but geography is the here and the now and here and now there are many many, too many Chanies dying, feeling lost and alone, a full fifty years after the Wenjacks were told their boy was found by the railway tracks,

While Downie and his crew of fantastic makers were out talking, promoting and performing the Secret Path project, a ten-year-old First Nation child from Deschambault Lake, SASK, committed suicide. Earlier this month two teens, one from Stanley Mission and another from the community of Lac La Ronge also took their own lives. Another twenty children are said to be at risk.

In Northern Ontario in the community of Attawapiskat there is also an ongoing suicide crisis among the young. Graveyards in First Nations communities across Canada are filled with the young. The Assembly of First Nations Chief Perry Bellegarde says aboriginal youth suicides are five times the national average.

At the end everyone involved in the project was brought onstage. Mike Downie, who first brought the story of Chanie to Gord was the MC. He had heard the story on CBC radio in a documentary by Judy Foster. Subsequently he read the piece written by Ian Adams for Macleans magazine in 1967. Chanie’s story had been told, it had been known but it was pushed away like so much snow down the embankment of history.

Adams was asked up onstage and he joined thirty six members of the Wenjack family along with the musicians, filmmakers and the illustrator for a final bow. Pearl Achneepineskum, Chanie’s oldest sister, sang a healing song, a sorrowful refrain for the boy in Fiddler’s Green. Chanie’s favourite song Ashes of Love was played over the speakers.

Mike Downie spoke about education being the answer and recently on Oct 17 and 18 educators from across the country met in Ottawa to plan a curricula around the Secret Path and the new Gord Downie Chanie Wenjack Fund (proceeds from all Secret Path projects will be used for other Truth and Reconciliation purposes).

Downie announced onstage that education of residential schools, cultural genocide and the legacy left on First Nations will begin in schools nationwide in 2017.

During the performance Gord Downie didn’t speak much, mostly allowing the work to speak for him. But the poet laureate of the hockey rink did break his silence to say “Let’s not celebrate the last 150 years, let’s just start celebrating the next 150 years. Just leave it alone.”

And then they all left us alone, with our thoughts and I thought about my own upbringing in Ireland in the 70s in a Christian Brothers School, the abuses meted out, the systemic collusion between church and state to cover up and my own desire to flee as far and as fully as possible.

And I thought about Chanie’s last moments and I imagined him to be happy, he had chosen to run, to keep his identity, to keep on his own secret path and the immense inner strength he must have had to have gone as far as he did.

I thought of the secret path the First Nations and colonized peoples everywhere (the Halluci-nation of A Tribe Called Red) have been walking on for centuries and the strength they have to keep on maybe for the next 150 years.