Oshawa 60s progressive rock groups Christmas, Spirit of Christmas and Reign Ghost will be inducted into the Oshawa Music Awards Hall of Fame on Saturday Apr 25 2020. Livestream available here.

By Gary Genosko

Guest Writer

Canadian singer, songwriter, and guitarist Bob Bryden has been in the record business in Canada for 50 years. By the time he was 19 years old he had put out four of the most celebrated psychedelic albums in Canada with his bands Reign Ghost and Christmas, released between 1969 and 1970. Subsequently, he has enjoyed a career as a producer and solo artist.

The known repertoire of Christmas – originally named The Society for the Year-Round Preservation of Christmas – consists of just four albums: the self-titled first album from 1970; in the same year, Heritage; and then the final album of the period, the fully progressive Lies to Live By – the last gift placed under the Christmas tree, if you will, in 1974. Later, in 1989 Bryden released his own mix of Christmas Live, featuring material from a 1971 show in Toronto, warming up for label mates Crowbar.

There is, however, something missing in this discography; a masterpiece that has been the stuff of rumour. Together with Bryden’s assistance, I went in search of what remains of the legendary Christmas masterwork, Black Winter.

‘Maybe Black Winter was meant to disappear’, Bryden recently reflected on what for him is a truly lost piece of music from the period following the release of Christmas’s Heritage album in 1970. The song was performed live from around 1972-73, prior to the reformation of Christmas as The Spirit of Christmas. He dates the composition of the song to 1971.

Black Winter would not have been out of place on Lies. There are dark themes of scientific and technological catastrophe unfolding in songs such as ‘The Factory’, as mass-produced test tube babies roll off the line and out the door. Christmas was formed and thrived in the factory town of Oshawa, about 50 kilometres east of Toronto, where the General Motors plant sat at that time like a brick cathedral in the downtown. It was a hard place for countercultural youth to find their voices, but the music scene was one place of respite for Bryden and his bandmates, not to mention their fellow musicians who had invaded the coffee and tea houses that once hosted the folk circuit.

Painter and designer Gary Gatti’s cover painting for Lies, commissioned by Frank Davies of the record company Daffodil, and executed after hearing the complete pre-released recording, stays close to the themes of nuclear peril, cloning, social indifference, and war both modern and ancient (Greco-Persian to be exact and the Battle of Thermopylae). ‘I painted what I heard’, Gatti explains simply and to the point.

The fact that Black Winter is lost should raise a few eyebrows, however, since Bryden is the consummate archivist, and recently released four ‘abandoned’ songs from the post-Heritage period on Abandoned Songs and Living Room Jams in 2018, with collaborator Rory Quinn. A fragment of Black Winter can be found there in an unlisted, hidden track on the CD, number 13, ‘Deviled Buzzard Eggs’ from the original song’s epilogue. This ominous yet absurdist short song, never before recorded, about the handling and hatching of buzzard eggs, provides an ambiguous clue to the ending of Black Winter. ‘I originally saw it as a non sequitur ending – like McCartney’s ‘Her Majesty’ on Abbey Road’. It probably would have been a hidden track on a Christmas album which never happened’, Bryden specifies.

Today, Bryden claims to only vaguely recall a few riffs of Black Winter, a song that stretched to 45 minutes when performed live. Yet it was supposed to become Christmas’ major statement concept album with the kind of ambition that Jethro Tull’s Thick as a Brick displayed. ‘It was to be our Tommy’, Bryden reflects, an impactful musical event with enduring pop cultural significance.

What happened to Black Winter?

With a little encouragement, Bryden scoured his personal archives for some trace of the high concept that never made it onto vinyl and has left barely a trace.

Apparently presented for students at a suburban high school in Whitby, Ontario, the town just west of Oshawa, Bryden recalls the degree of alienation produced by the performance. ‘We alienated them COMPLETELY. It was a very “straight” crowd and they sat or stood around the walls of the auditorium aghast, as we rolled through Black Winter and other snappy tunes’. Bryden adds that one of the band’s most avid fans at the time, Jerry Ames, came backstage after the show ‘to lecture us on the necessity for such an overwhelmingly grim piece of music’.

Bryden ties the failure of Black Winter to the fate of Lies. ‘Lies stiffed because it is was so dark. Canada wasn’t ready for anything starless and bible black – although it does end on a Tolkieneseque high note (Lord Dunsany actually). Had Christmas continued our next album would have made Lies look like Top 40. A 45-minute song about the world after nuclear war’.

The band had already used the sound of a nuclear explosion at the end of ‘The Factory’ on Lies, a two-part opus about dehumanization. The first part, ‘Where the People are Made’, describes the serial production of human life, and the second, ‘Everything’s Under Control’, a tour of the factory with statements by the foreman, district supervisor, and a smothered human being struggling for air. Invoking Irish fantasy writer Edward Plunkett’s (the aforementioned Lord --and Baron) later novels about the rise of machines, Bryden’s writing is full of highly nuanced literary and cinematic allusions, while attentively exposing the death spirals of the twentieth century. Bryden’s attachment to bleak themes was not without some sense of recovery, perhaps not resolution. In a word, his bleakness was not inexorable.

Until Black Winter, that is. Black Winter is symbolically signalled by the nuclear explosion at the end of the song, ‘The Factory’.

Digging deeper, Bryden came up with two original documents that help to shed some light on the lost work.

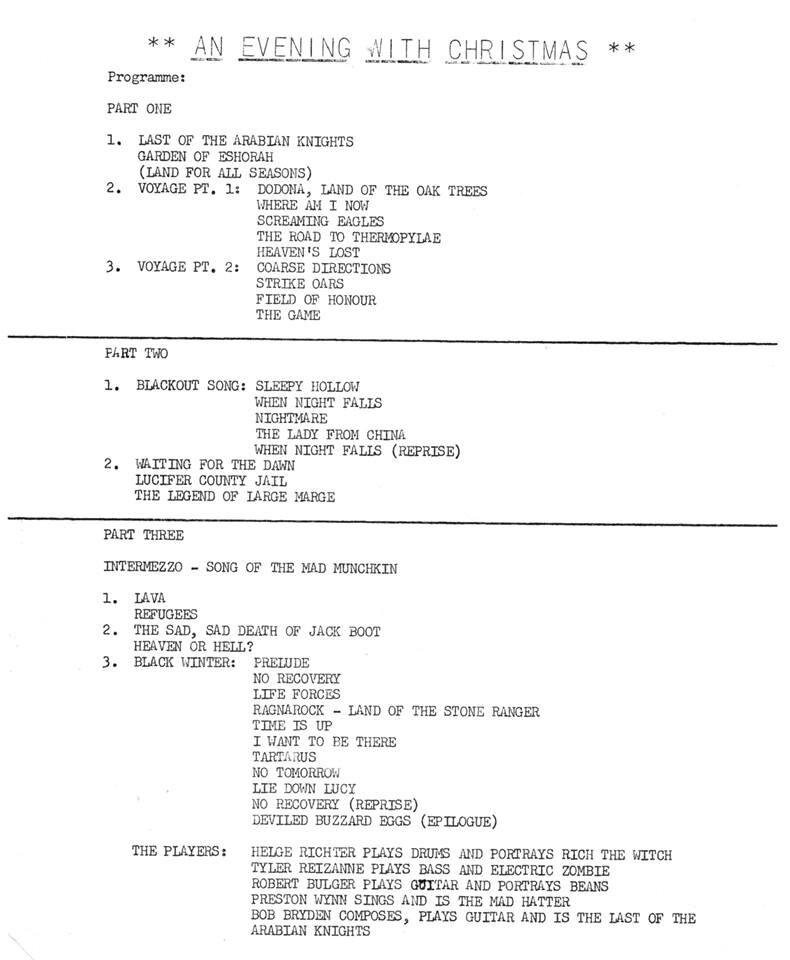

The undated programme titled ‘An Evening with Christmas’ accompanied the performance of the piece. Black Winter rounded out the third and final section of the performance. It was put together as a long-form progressive opus with a prelude, and epilogue (‘Deviled Buzzard Eggs’). It contains a reprise of the first section, ‘No Recovery’. The sections follow in order: ‘Life Forces’; ‘Ragnarock – Land of the Stone Ranger’; ‘Time Is Up’; ‘I Want to Be There’; ‘Tartarus’; ‘No Tomorrow’; and ‘Lie Down Lucy’, followed by the aforementioned reprise, and epilogue. However, the third section of the performance begins with material that was released on Lies, specifically ‘War Story’, inspired by Stanley Kubrick’s film Paths of Glory (1957) and the horrors of trench warfare in World War I.

There is more. Sometime during the 1990s, Bryden had put together all of the scraps he had in his possession from the complete Black Winter, and on a single page wrote them down for posterity. Although the opus is condensed, and it remains difficult to appreciate the overall reach of the piece, there are a few hints about what he was up to at the time.

A few of the original themes are evident, especially his use of the Norse myth of the final battle (Ragnarock) in which heroes (like Thor) meet their demise. Of course, here it is not the mighty yet imperfect god, dispatched to live among humans on earth. Rather, it is the character Lucy, and her fate on an ‘eastern’ (Saracen) road, in the surviving fragment of the chorus. And the first section, ‘No Recovery’, is perhaps the most complete, as the gloom is spread thickly in the repetition of a hopeless end of time scenario: ‘There will be no recovery … When the black winter comes…’.

There is a proto-punk sensibility in the compiled fragments of Black Winter with the exclamations of ‘no tomorrow’ that would have been out of place in early 1970s, but de riguer by the time the Pistols arrived. The imminent death of the narrator, ready to face the inexorable arrival of black winter, and join his character Lucy in a future without hope, is a grim prospect by any estimation.

The summer of love may have evaporated by 1971, but the summer of hate had not yet arrived. It wasn’t until 1977 that Johnny Rotten screeched No Future! Black Winter pointed the way towards it in an original fusion of prog and punk.

The former bassist for Christmas, Tyler Raizenne, brings the subject matter of Black Winter down to earth from its lofty metaphysical heights. He explains that the neighbourhood in Oshawa where he grew up was near an iron factory known as Fittings Foundry. ‘They used silica sand in the process and in the winter the snow around the plant would be black’. The reality of industrial Oshawa for those living there in the post-war period was sufficient to evoke a blackened winter of unchecked industrial pollution.

The search for the complete Black Winter continues.

***

All lyrics and documents are the property of Bob Bryden and used with his kind permission.

Gary Genosko is the independent curator of Psychedelic Oshawa *Robert McLaughlin Gallery, 7 February-12 March 2020) and Professor of Communication Studies at OntarioTech University in Oshawa, Canada.