Retired General Romeo Dallaire’s brutally honest memoir recounting his two decades long battle with PTSD is mercifully slim, just 184 pages. Mercifully because "Waiting For First Light", published by Random House Canada, is a harrowing read.

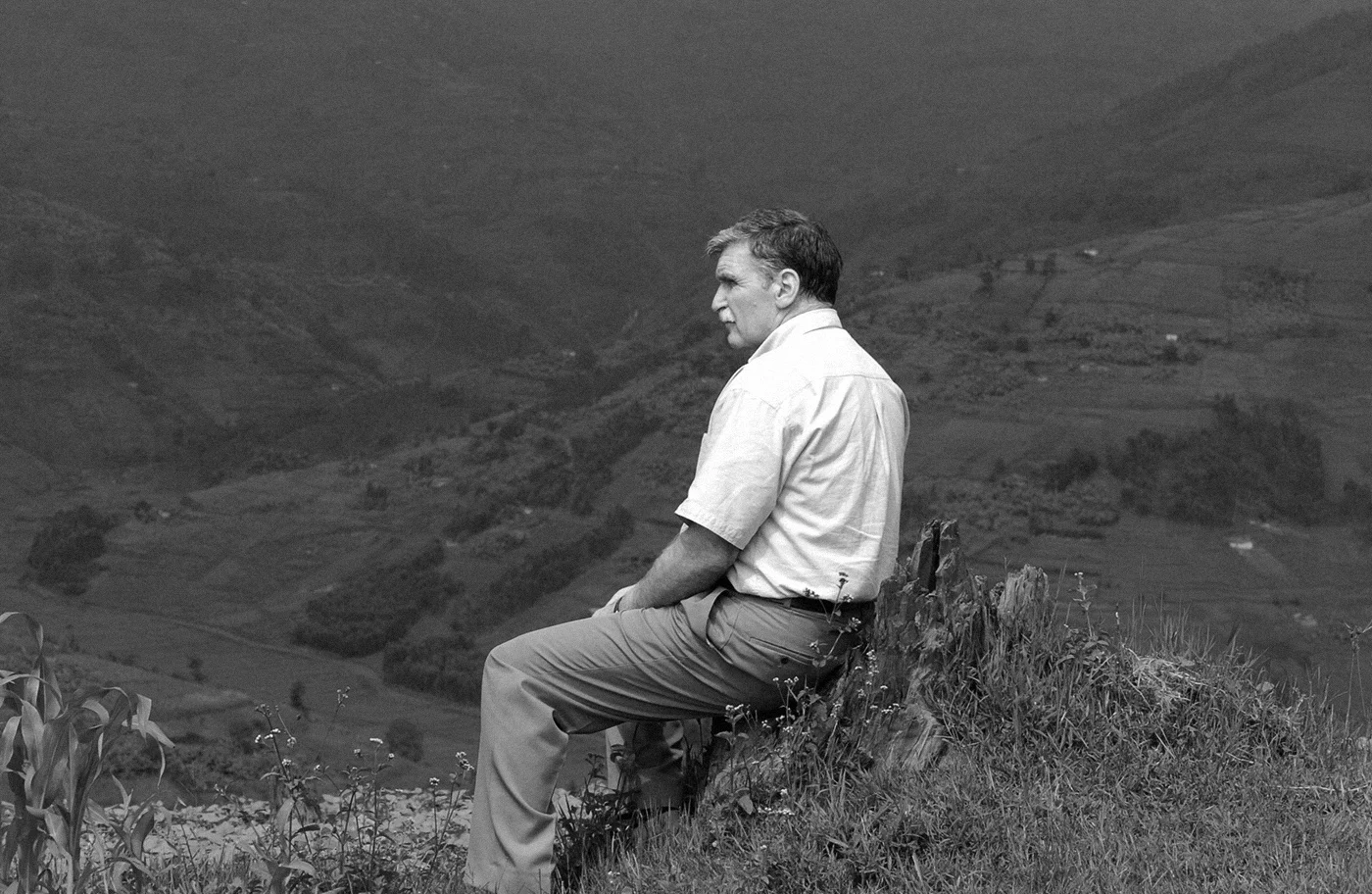

Gen. Dallaire was the commander-in-chief of the United Nations peacekeeping forces in Rwanda during the 100 day genocide in 1994. 800,000 were slaughtered. Dallaire was under orders to not intervene but he defied the command to protect those seeking safety in the UN compound. He is credited with saving 40,000 lives but for twenty-two years he has lived with the guilt of his and the world’s inactions. Like the mythological Sisyphus, Dallaire is condemned to relive his time in the east African country over and over again. He is reminded constantly of the horrors he witnessed.

He self-medicated his trauma with alcohol; there were several suicide attempts and subsequent therapy sessions. But mostly he dealt with the PTSD by delving deep into his labours, much of it voluntary, from early in the morning until dawn the next day, staving of the nightmares, waiting for first light when he could sleep, perhaps, for a time.

While the purpose of the work was to preoccupy his mind the work itself was purposeful and important. He founded The Roméo Dallaire Child Soldiers Initiative. He wrote two award-winning books “Fight Like Soldiers, Die Like Children” and “Shake Hands with the Devil: The failure of humanity in Rwanda”. He was appointed a senator and he became also an outspoken advocate for soldiers with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. This book is part of that speaking out.

PTSD is a hidden injury, in a way a wound not even considered an injury but more of a symptom of the soldier’s unfitness for the theatre of war. As war becomes more and more personal it is an injury on the rise.

When Dallaire’s workload lessened he would walk at night through darkened parks and laneways, hoping to be robbed and murdered. Such a death would be deemed more honourable he thought for a career soldier than by his own hand. Although he did attempt suicide Dallaire credits his ineptitude at that task as the main reason he is still alive.

Alive perhaps but not living. By the end of the book we realize all has changed, changed utterly for him. Dallaire lost his own life in the genocide. He went in and he never came back. His wife and his children have lived with the loss, as have his friends and his assistants. His PTSD impacts them all and it is a further tragedy that the genocide continues to maim and claim victims, so many years after.

I suspect Lieutenant-General the Honourable Roméo A. Dallaire, O.C., C.M.M., G.O.Q., M.S.C., C.D., (retired) has managed so far because he is just that, an honourable man. He has fought his own demons, he continues fighting them, because, regardless of what he witnessed, he hasn’t given up on humanity yet. His hope by telling his story perhaps, is that we have given up on him either. And we haven’t.

Listen to Carol Off speak with Romeo Dallaire on the CBC radio show As It Happens

In “The Wars” Timothy Findley also wrote of war inflicted PTSD. I would suggest it as a companion read to Dallaire’s demanding but rewarding story.